Water War Mural in Cochabamba, Bolivia

This mural in Cochabamba, Bolivia, was created in as part of the events marking the 10th anniversary of the The Water War, in which the local population rose up and reversed the privatization of their water supply and its takeover by the multinational Bechtel.

In order to reaffirm their defense of water as a common good, a series of grassroots events marking the anniversary of the uprising were organized in April 2010. They were hosted by the Federation of Factory Workers of Cochabamba, and by AsicaSur, the association of the community-run water systems of Cochabamba's southern and most deprived neighborhoods, called the Zona Sur. These organizations and La Fundación Abril are the direct legacy of the water war, and we were honored to be invited to make art for this occasion.

Prominent water warrior, labor organizer and Goldman Prize winner Oscar Olivera, and La Red VIDA coordinator Marcela Olivera invited Mona Caron and David Solnit on behalf of AsicaSur, the Coordinadora Del Agua Y De La Vida, and the FWW, to contribute visuals for the occasion, including this mural.

The mural was titled “La Lucha Por El Agua Continúa”, and it describes the coming together of different sections of the population in the struggle, as well as the sustainability issues still present in the aftermath.

Location context

The mural was painted by the entrance to the headquarters of the Federation of Factory Workers of Cochabamba, tying the pre-existing lettering "Complejo Fabril Cochabamba" to the entrance gate.

The Complejo Fabril was the site of the Feria del Agua, a water fair by and for the remarkable community-run water systems of the Zona Sur. It was also the point of arrival of a massive march through the city of Cochabamba on the anniversary of the uprising, and it also hosted an international conference on water rights the following week.

The mural imagery

The many active groups that were part of the uprising came from 3 geographically distinct areas, represented within the three ribbons that interweave to represent the historically exceptional unity that Cochabamba was able to achieve in the period of the Water War of 2000.

The first, red ribbon, which starts from the "complejo fabril" sign, represents the urban participants of the uprising. These ended up encompassing the working class, the middle class as well as the church.

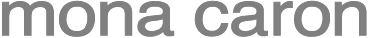

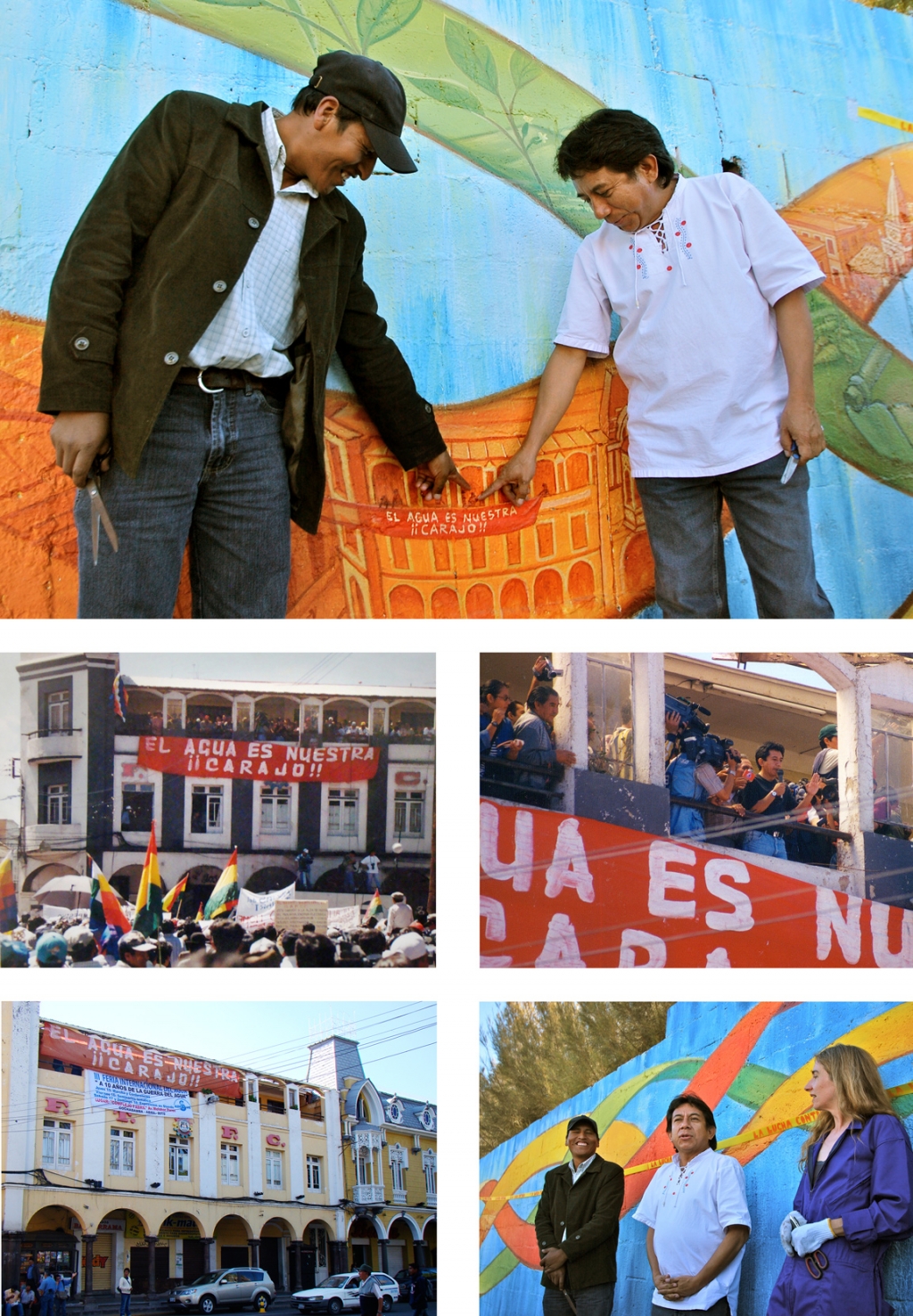

The Federation of Factory Workers played a central role, and ignited the uprising when they hung, from their balcony on the Central Plaza, the famous red banner “El agua es nuestra, carajo!” The banner’s appearance marked the moment in which the urban areas joined the countryside in resistance to the privatization of the region's water supply.

In the picture below, Oscar Olivera (right), the leader of the Federation at the time, and Abraham Grandydier of Asica-sur, point to where they were standing at that historic moment: the balcony of the union building from where they spoke to the crowds.

The second, green ribbon represents the distinct rural groups that united during the rebellion: from the federation of land irrigators (represented by the landscape of fields with irrigation canals) who were the first to rise up, to the campesinos of the mountainous areas (represented by the Maiz, potatoes and quilquiña), to the cocaleros from the Chapare region (represented by the coca leaves).

The third, yellow ribbon represents the dry, waterless, and vast Zona Sur, which is settled in great numbers by former miners from Potosì, as well as by former campesinos. These thoroughly organized communities built their own water storage and distribution systems there, autonomously, because neither private nor government entities would provide them with basic infrastructure.

In the photo below, Don Filemón of the water cooperative "22 de Abril" of the 14th District of Cochabamba in the Zona Sur, points to his cooperative's water tank, which he had taken me to see. Below the tank, entire families with pickaxes are working to build the road leading up to the tank.

The moment of the water war itself is represented by the barricade. The Bolivian flag was widely used during the uprising along with the Whipala (the indigenous poeple’s flag) by the people on the barricades. The weapon of choice was the slingshot.

Behind the barricade, the water-colored background becomes turbulent, symbolizing upheaval, and the spreading of the struggle far beyond the local area.

After the turbolence, at the end of the mural to the right, the water calms down again, melting into clouds and a symbolic depiction of the scant and over-tapped water table under Cochabamba.

What happens after things calm down? What is the water situation now, 10 years later? As the waters calm, the city is painted as having water "roots" drawing from the water table below. Some roots, notably those near the southern, hilly areas, do not reach the water and turn brown.

At the end of the mural, to the right, a page leaf is turning: the end of the story, the end of the struggle for equitable access to natural resources, is not over. The story, and the struggle, continues.

Below: a slideshow of a few moments during the painting of the mural and of the opening party.

For an excellent brief history of the water war of Cochabamba , check out "Dignity and Defiance, Stories from Bolivia’s Challenge to Globalization" by Jim Shultz.

For an in-depth history of the water war, as told by one of its crucial participants, see Oscar Olivera's book, "Cochabamba."

Article by Raúl Zibechi, "Cochabamba, from water war to water management"

For up-to-date information on the work done by local organizations that are the direct legacy of the Water War, check out Fundación Abril. Internationally: La Red Vida

AsicaSur no longer exists by name, but their work continues, see Yaku al Sur.